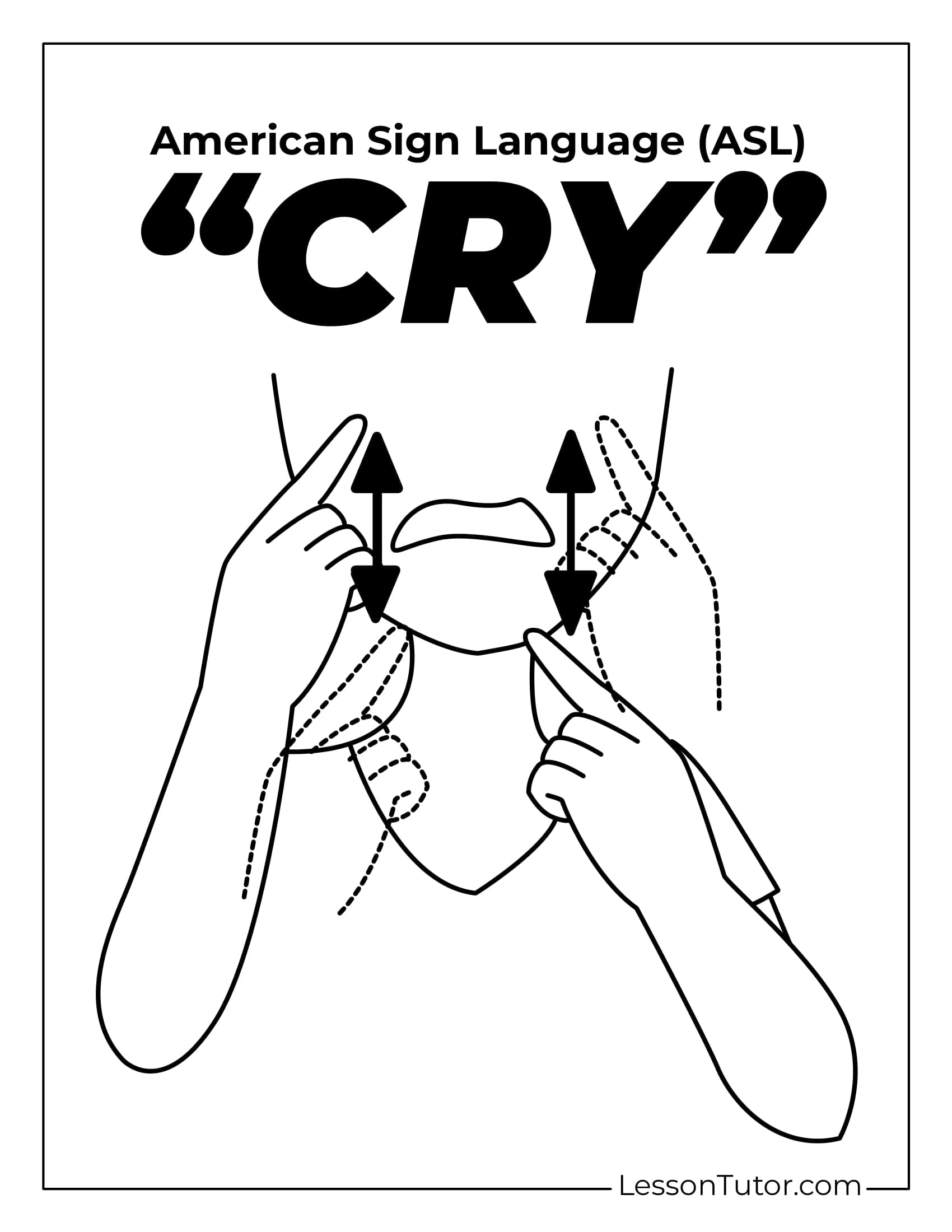

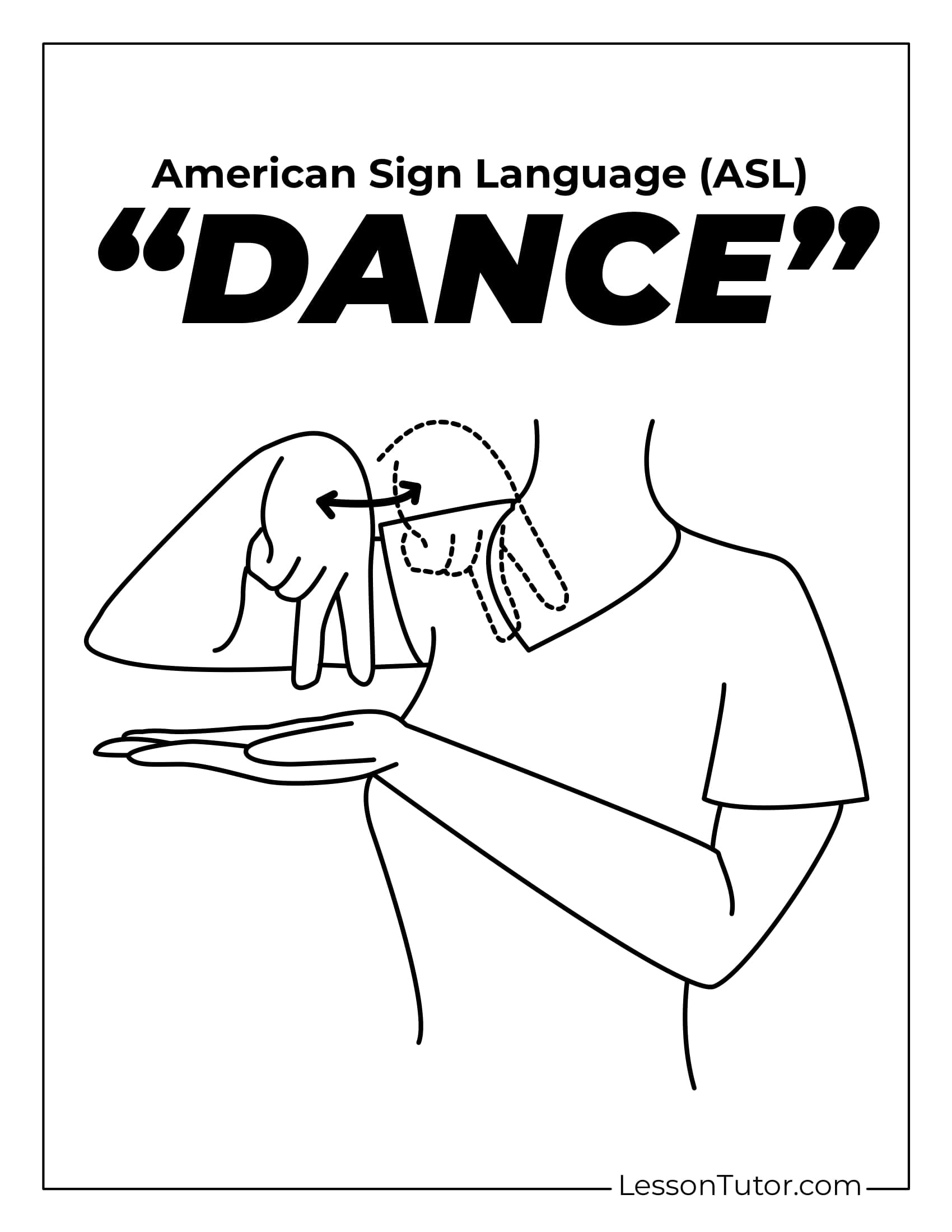

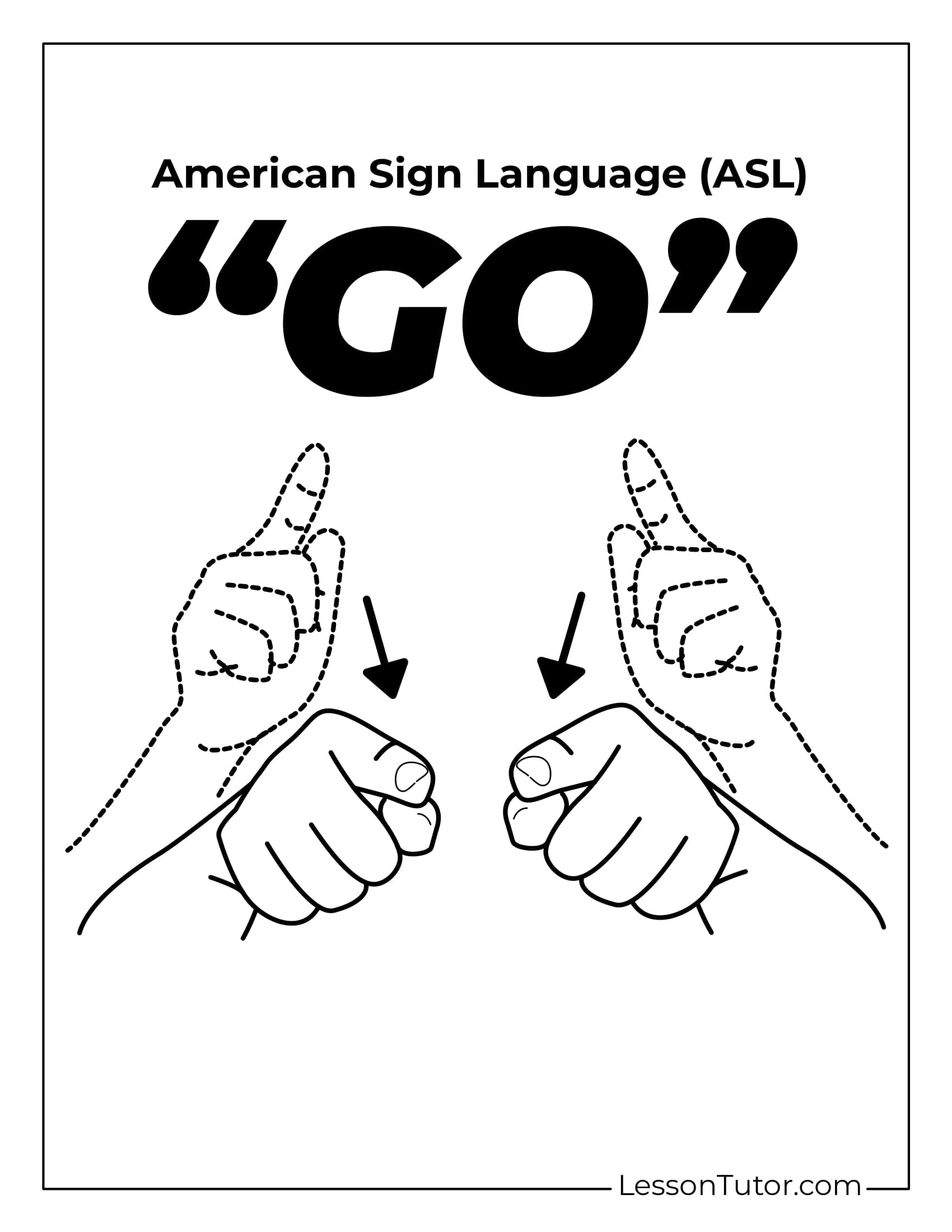

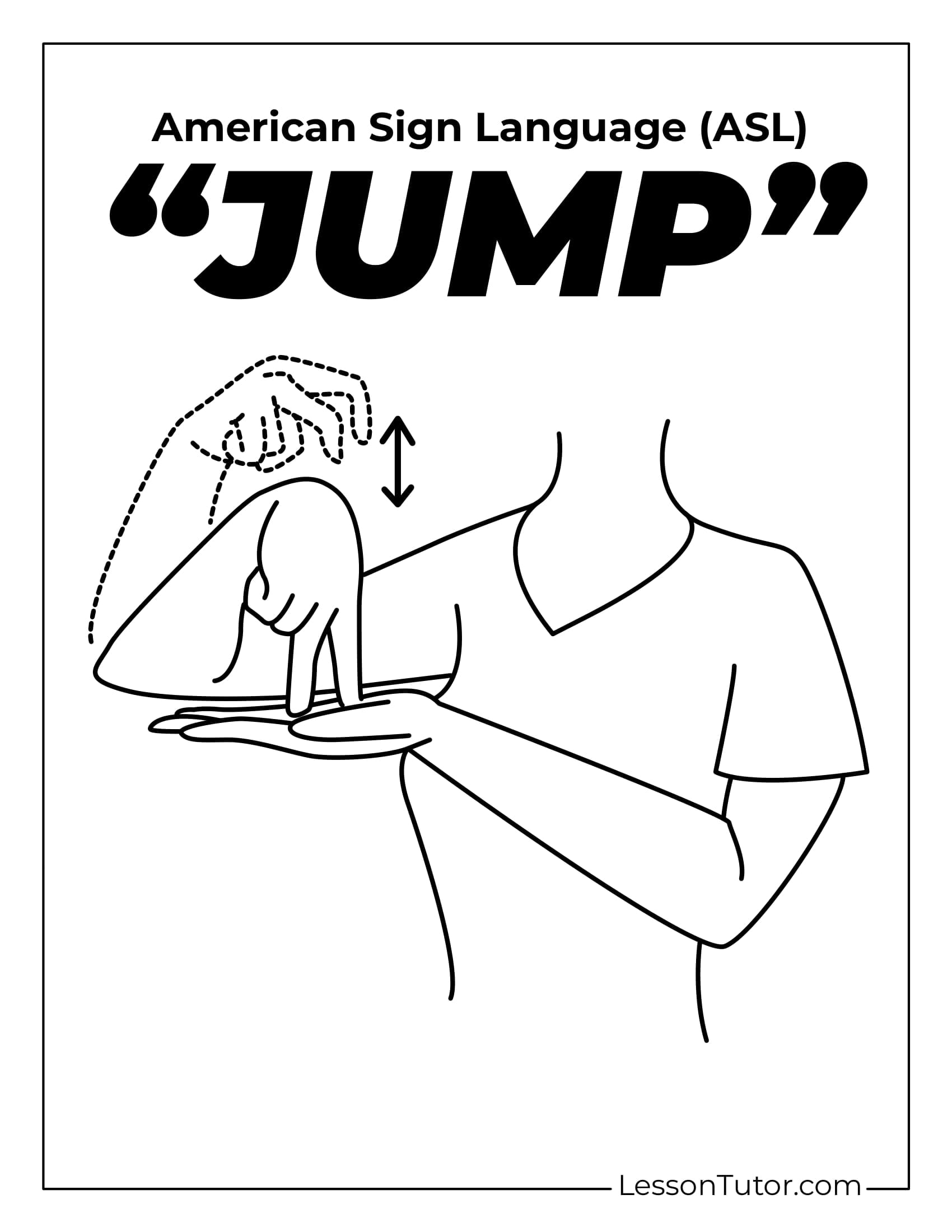

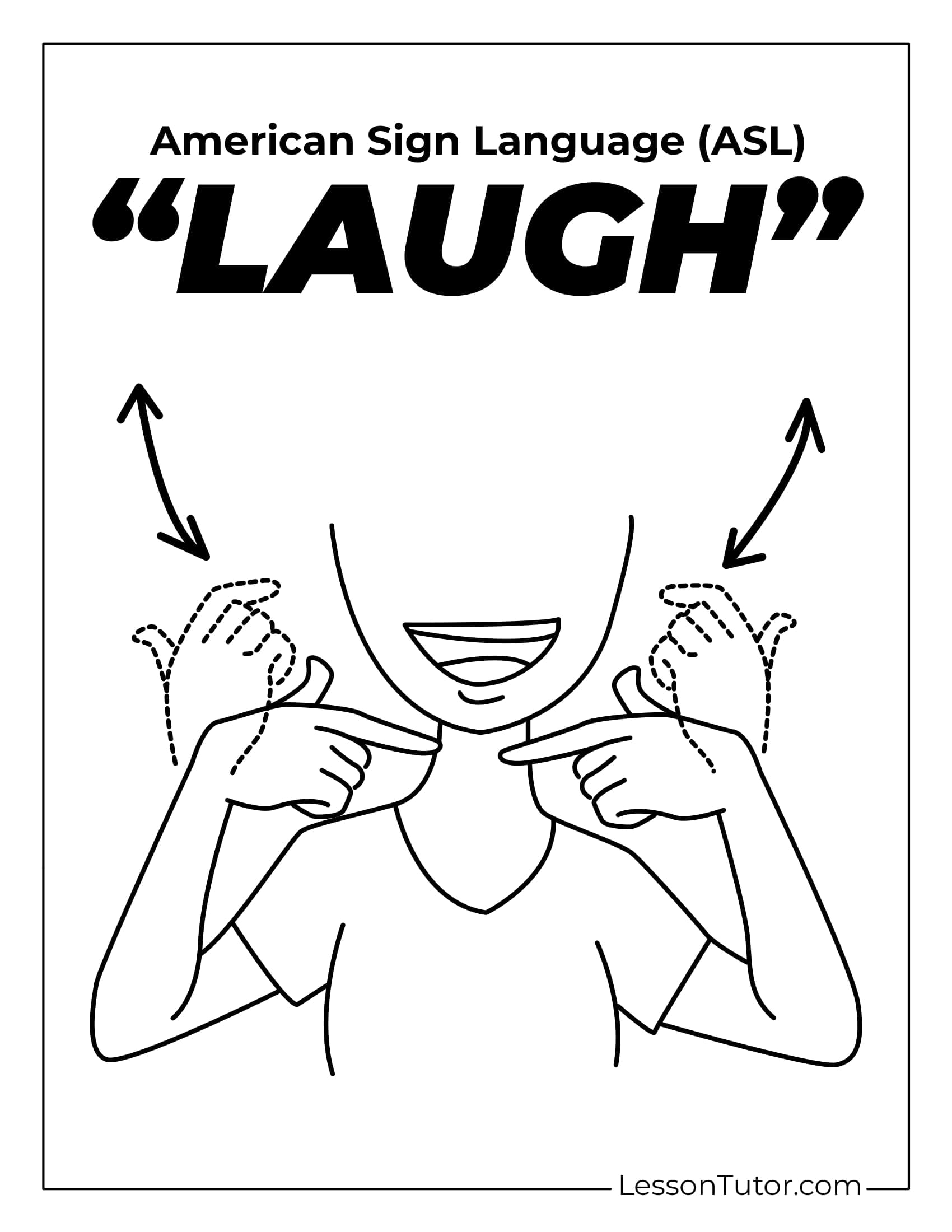

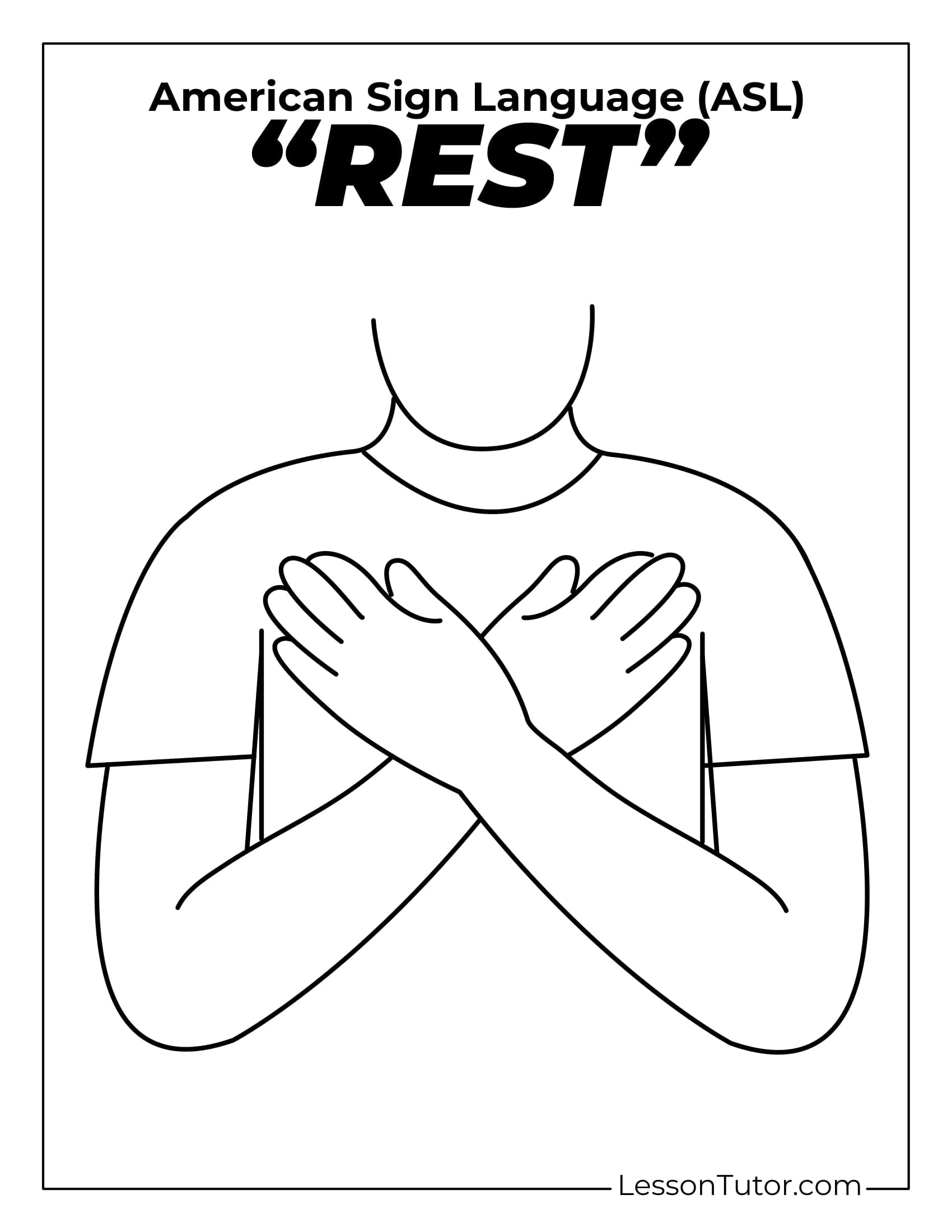

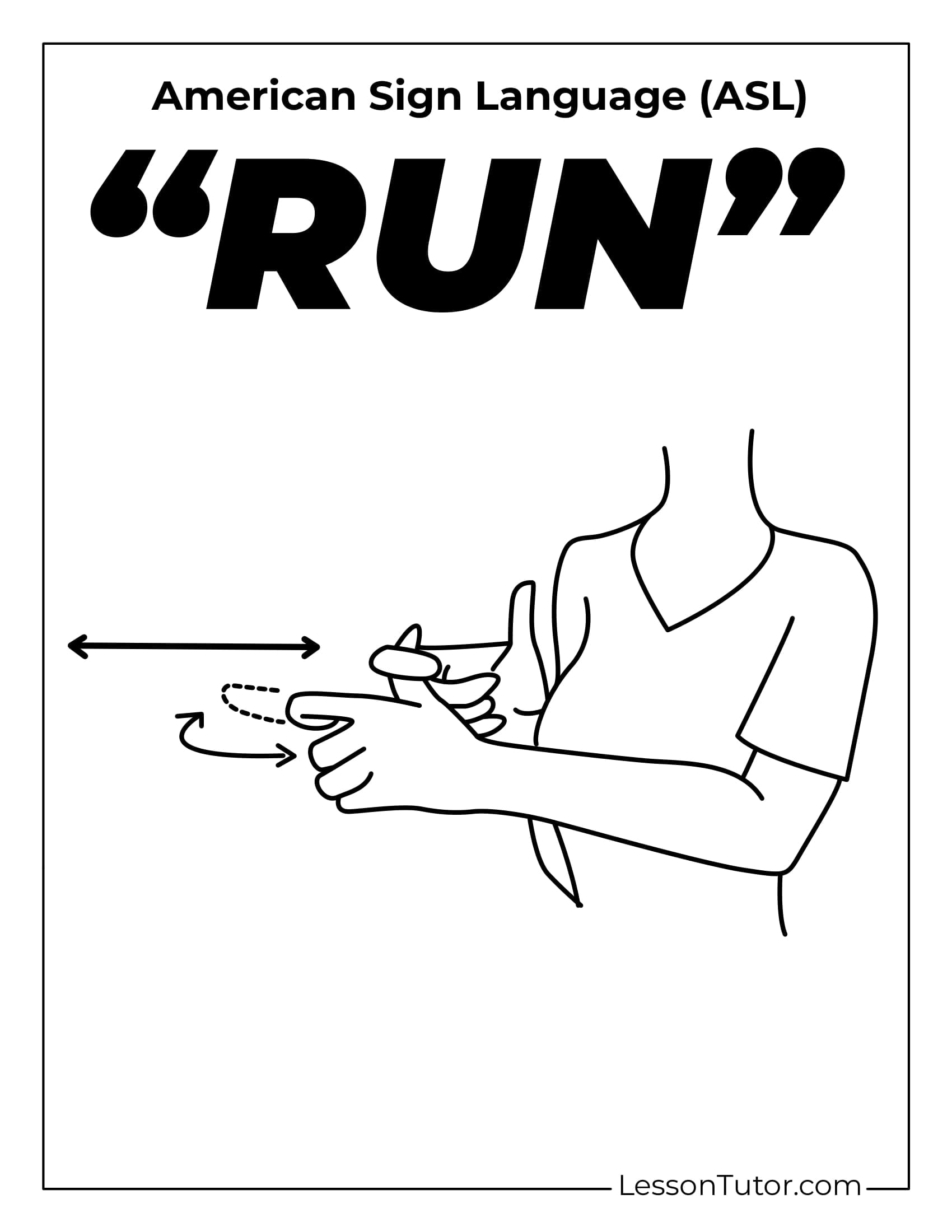

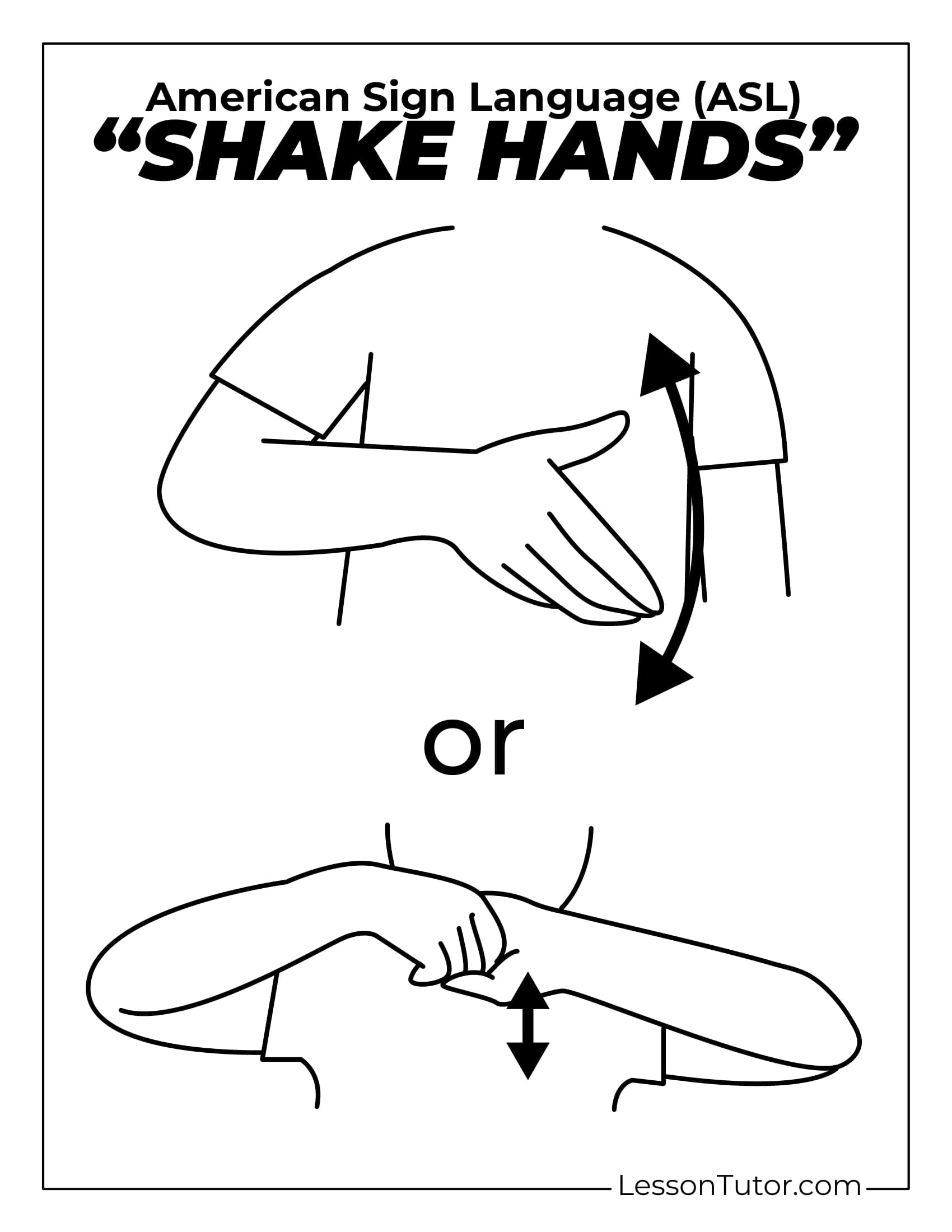

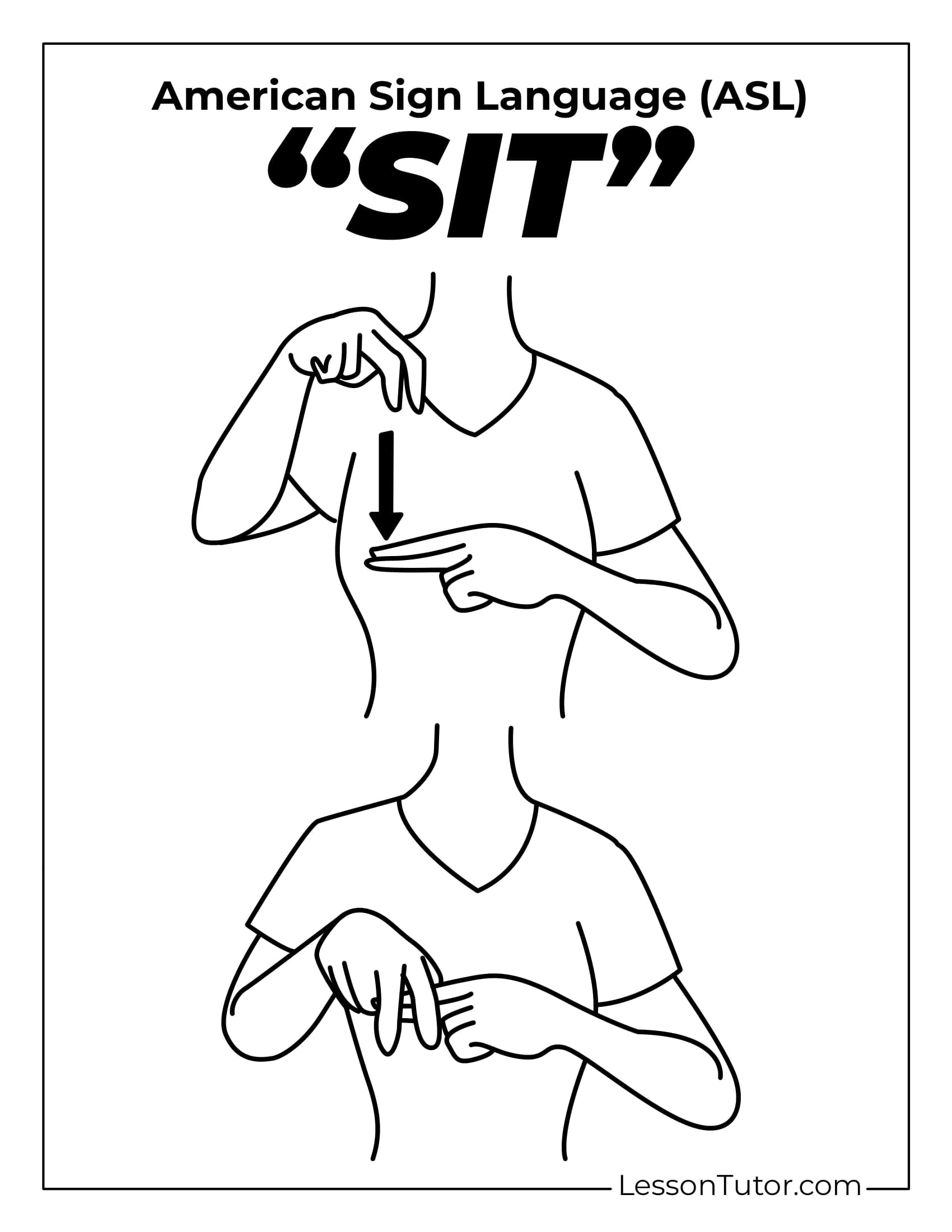

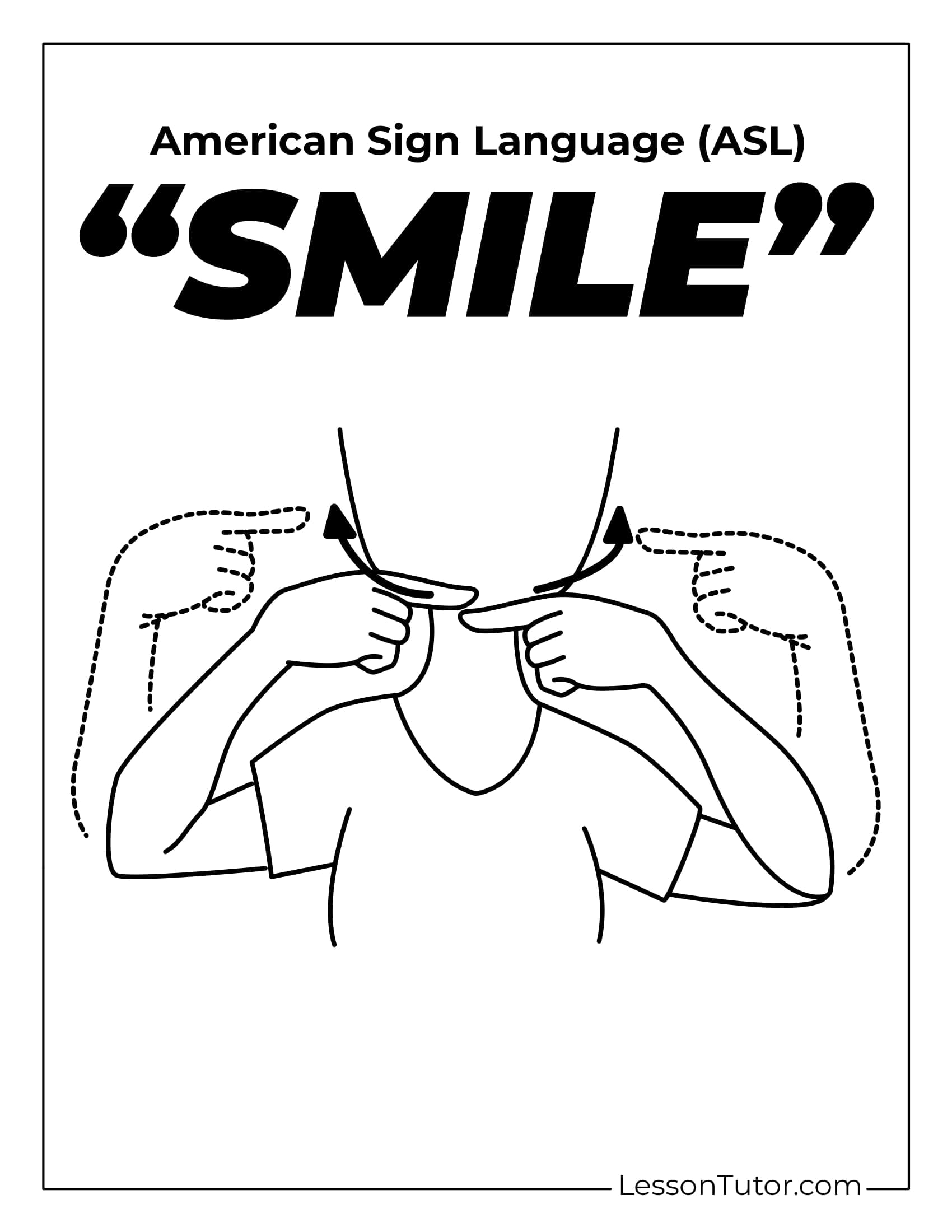

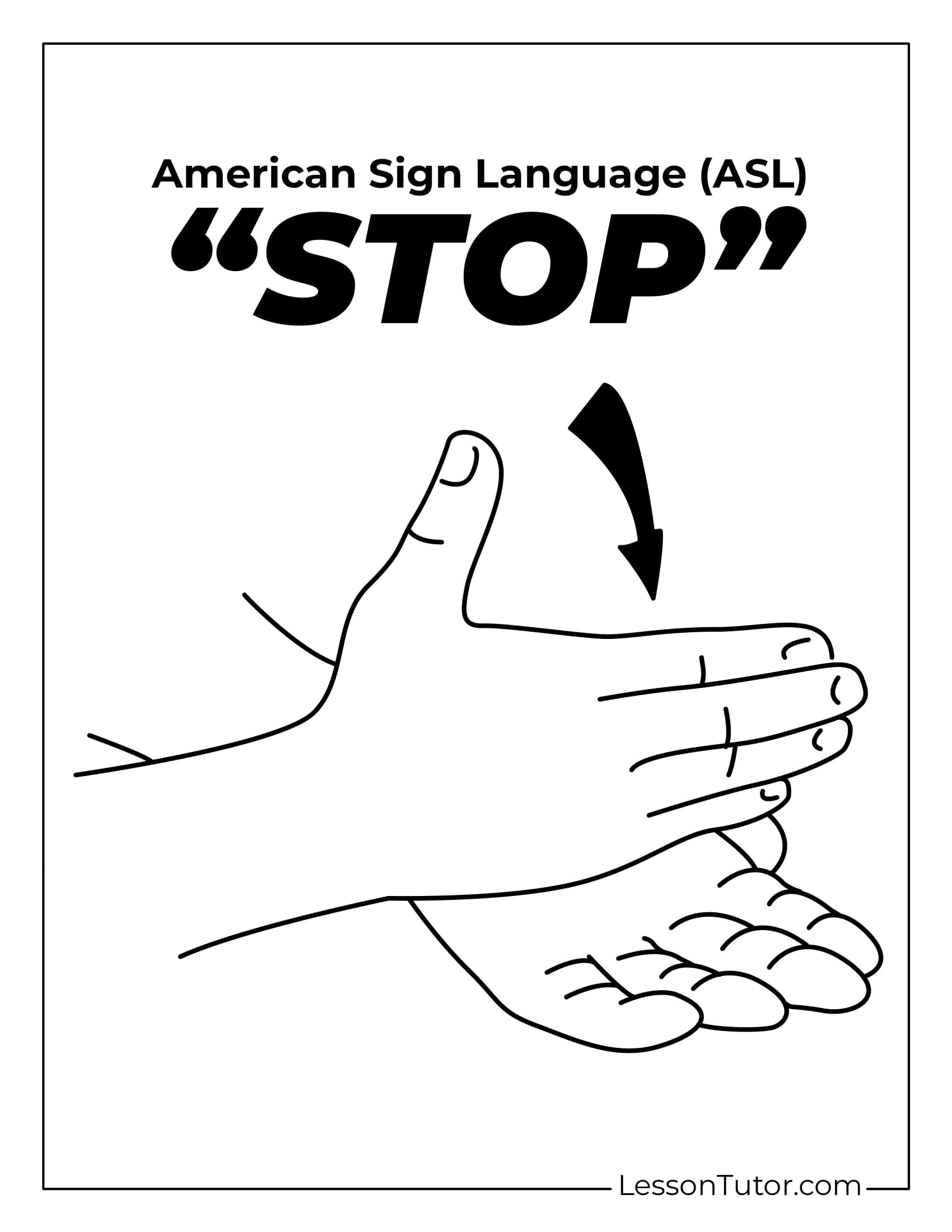

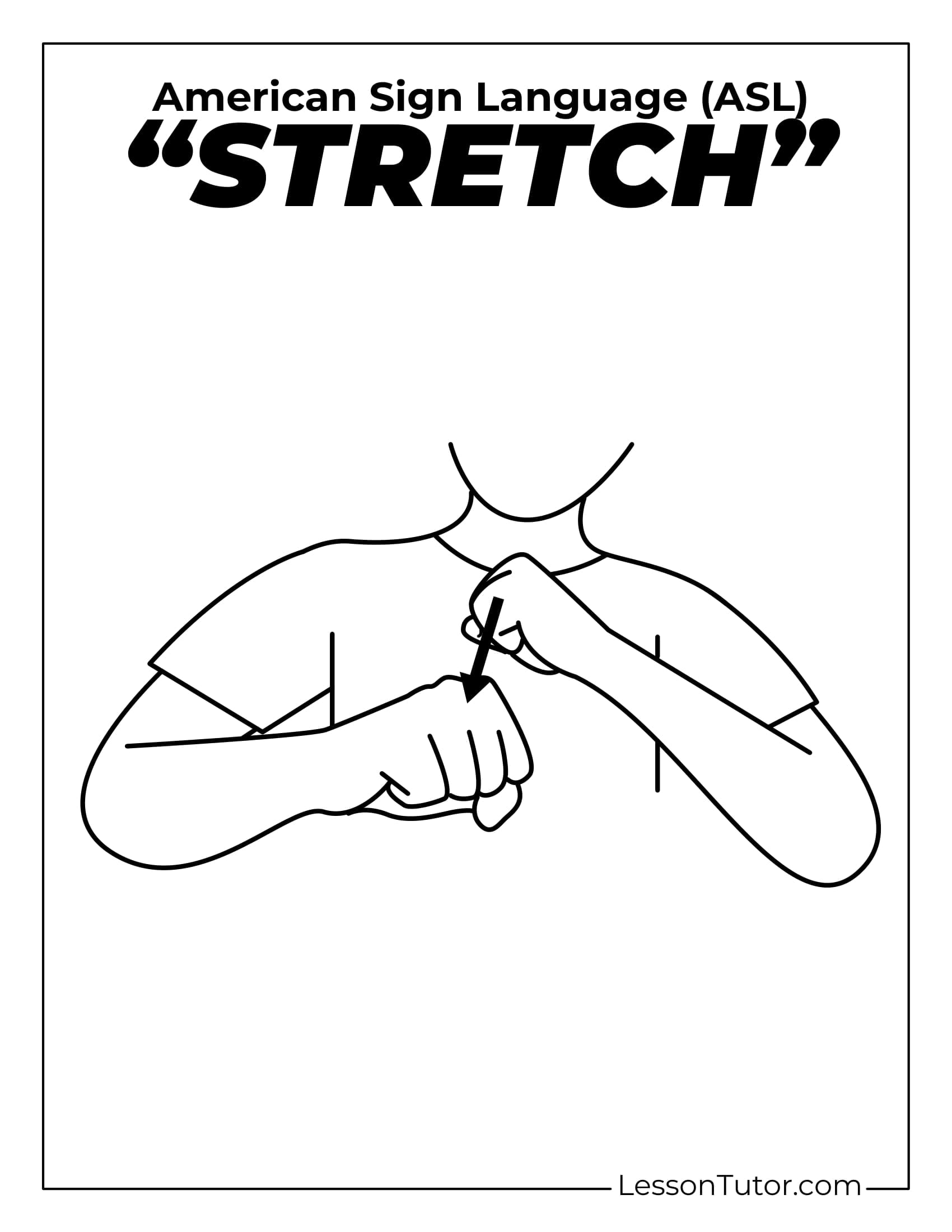

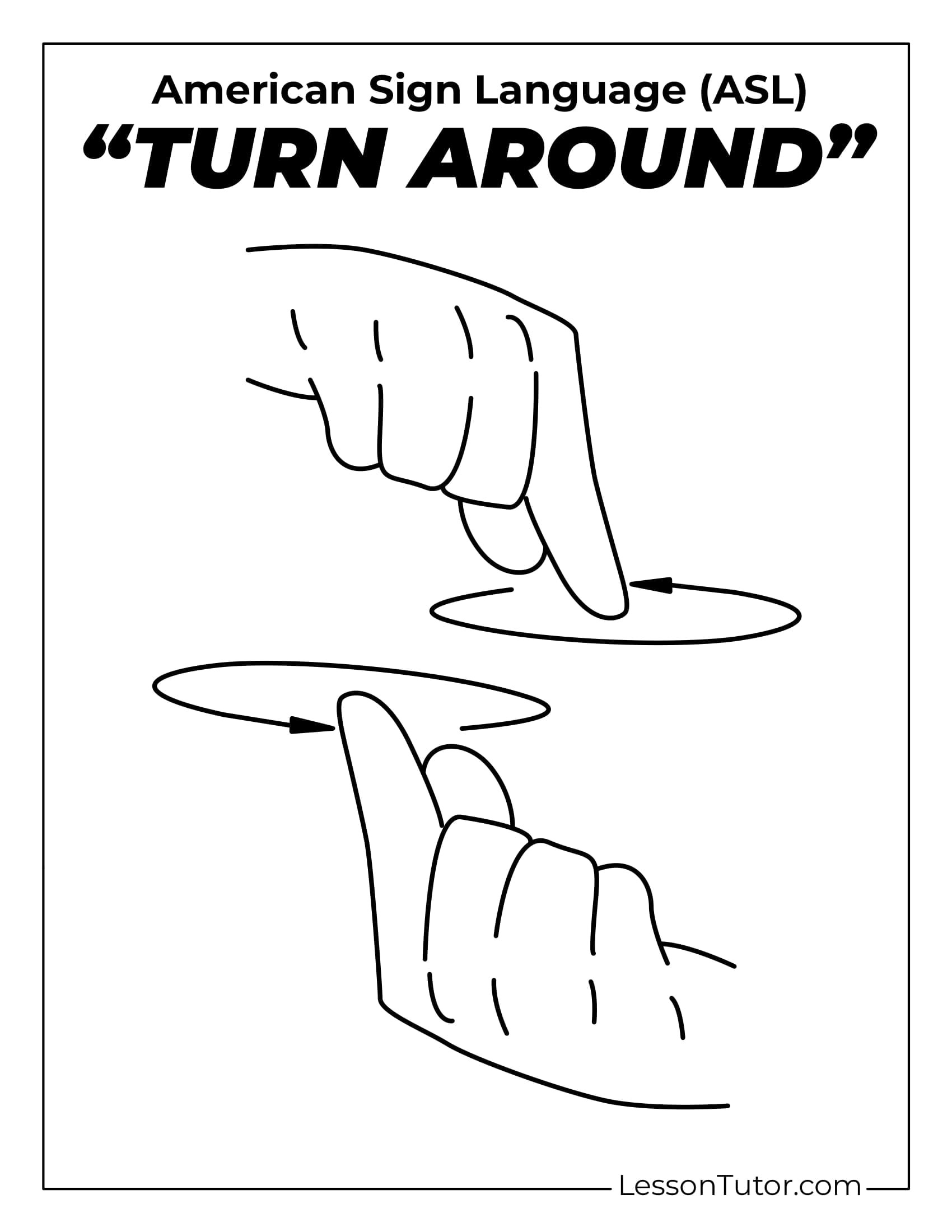

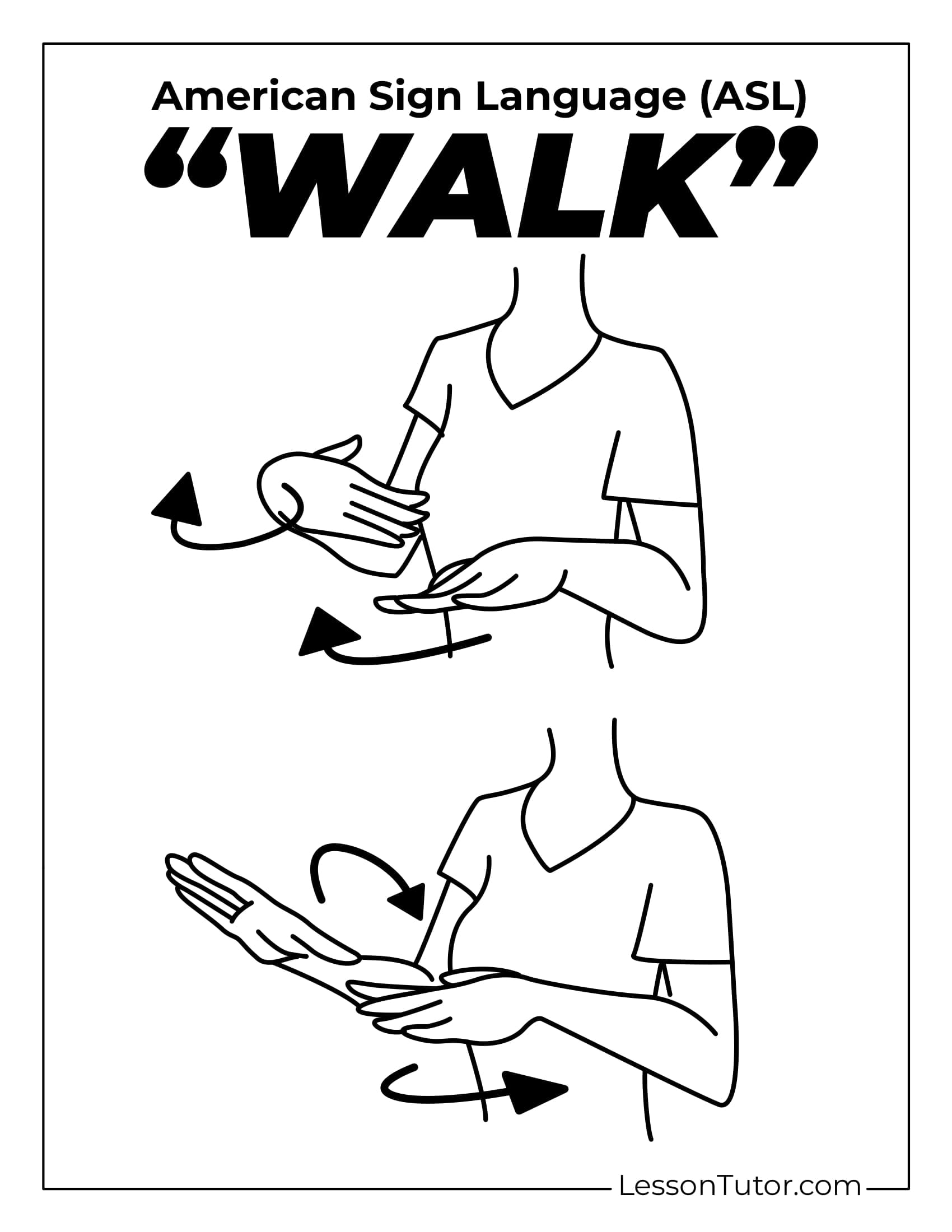

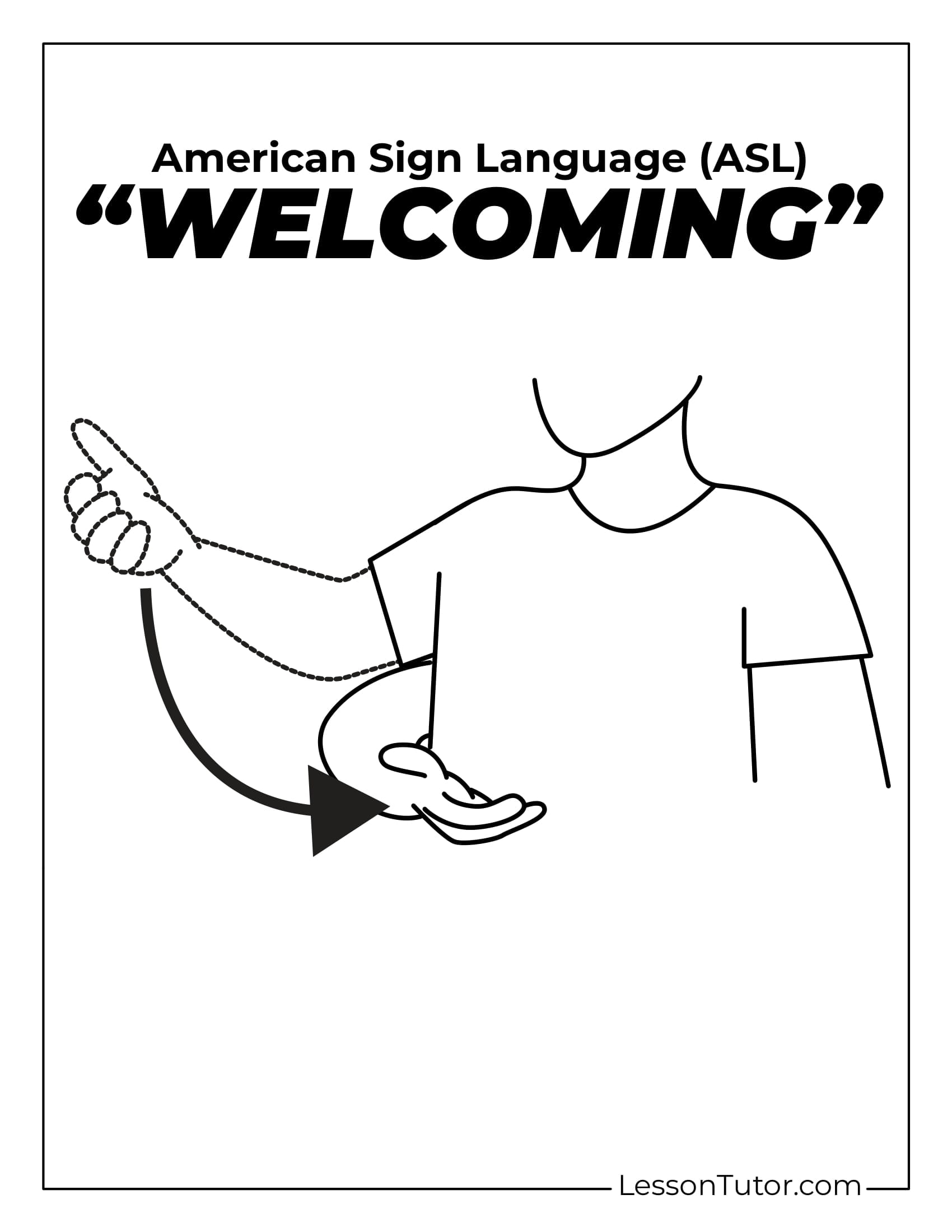

Discover the power of body language in American Sign Language (ASL) with this interactive collection of 15 educational worksheets, designed to teach essential movement-based signs in a fun and engaging way! This set introduces learners to key ASL signs such as Welcoming, Sit, Walk, Run, and Jump, offering a hands-on approach that’s perfect for classrooms, homeschooling, or self-study. With clear illustrations and activities that encourage practice, these worksheets help students build confidence while mastering everyday body language signs.

Designed for A4 paper sizes and free to download, these 15 high-resolution worksheets are an invaluable resource for teachers, parents, and ASL enthusiasts. Whether you’re introducing ASL to beginners or looking to expand your sign language vocabulary, this printable set offers a creative and effective learning experience. Download now and start mastering ASL body language with confidence!

Craft Ideas To Do With Body Language Worksheets

This comprehensive collection also includes signs for Dance, Stop, Go, Turn Around, Smile, Laugh, Cry, Shake Hands, Stretch, and Rest, covering a range of motions and expressions. Through tracing exercises, matching games, and movement-focused activities, learners of all ages can reinforce their understanding of ASL while improving their ability to communicate nonverbally. Whether expressing emotions or giving simple directions, these worksheets provide a practical and interactive way to learn body language in ASL.

More Free Printable Worksheets

If you're looking for more related worksheet goodies that kids love, we think you'll particularly enjoy these worksheet collections: